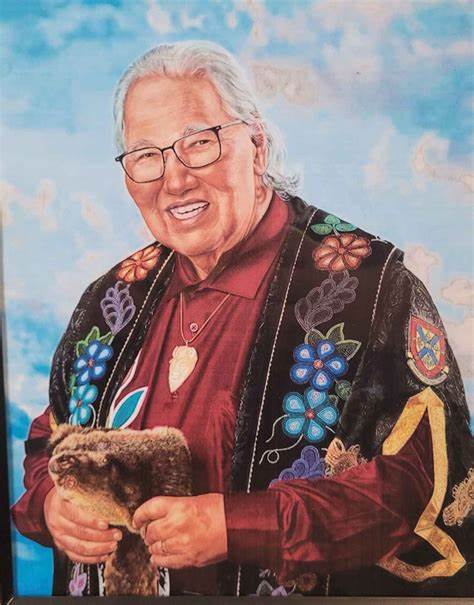

A father of five and a grandfather, Sinclair was a highly respected leader in Indigenous justice and advocacy. His work catalyzed significant reforms in Canadian policing, healthcare, law, and, most notably, Indigenous-government relations.

Sinclair’s family shared that he died “peacefully and surrounded by love” at a Winnipeg hospital. The statement highlighted his dedication, saying, Sinclair “committed his life in service to the people.”

Born on January 24, 1951, on a Manitoba reserve, Sinclair was raised by his Cree grandfather, Jim Sinclair, and Ojibway grandmother, Catherine, after his mother’s early passing. Both grandparents had been forced to attend residential schools.

Residential schools in Canada, government-funded institutions aimed at assimilating Indigenous children, sought to eliminate Indigenous cultures and languages.

Sinclair pursued law school in Manitoba at age 25 and worked as a lawyer for 11 years before becoming Manitoba’s first Indigenous judge and Canada’s second. He later co-chaired the Aboriginal Justice Inquiry of Manitoba and led the Pediatric Cardiac Surgery Inquest into the deaths of 12 children at a Winnipeg hospital. He went on to lead the TRC.

The TRC, a historic body in Canada’s recent past, issued its final report in 2015. Sinclair’s work with the TRC, including his conclusion that residential schools constituted “cultural genocide,” shifted Canada’s understanding of these government-run schools that left lasting scars on Indigenous communities.

Under the government’s forced assimilation policy, about 150,000 First Nations, Métis, and Inuit children were taken from their families between 1874 and 1996 and placed in state-run boarding schools. This policy inflicted deep trauma as children were compelled to abandon their native languages, adopt English or French, and convert to Christianity.

Sinclair found that approximately 6,000 children lost their lives while attending these schools.