The sun’s immense size renders the impact of solar wind loss negligible for it. In contrast, Earth is a relatively tiny entity, just three parts in a million as massive. While Earth’s magnetic field shields us from the solar onslaught, it is also pushed back by it.

Under specific circumstances, energy from the solar wind can permeate the near-Earth region, accumulating predominantly on the side opposite the sun, resembling a comet’s “magnetotail.”

This situation can become unstable when an excessive amount of energy accumulates, propelling particles into the nightside atmosphere and illuminating auroras. This clarifies why auroras are observable during the night—darkness prevails, and the sun’s energy takes an indirect route, initially storing in the magnetotail.

The rhythmic dance of auroras can also generate magnetic fields, potent enough to register on a compass, a discovery made nearly 300 years ago by the Swedish astronomer Anders Celsius.

If these magnetic fields undergo rapid changes, they can influence extensive Earth regions, culminating in issues for power networks. A notable incident occurred in North America in 1989, referred to as the “day the sun brought darkness.”

Solar Rhythms

In the early 1600s, Italian astronomer Galileo conducted a systematic study of sunspots. Nearly 300 years later, American astronomer George Hale revealed that these sunspots harbored intense magnetic fields, surpassing Earth’s strength by several thousand times.

Over the 400 years since Galileo’s pioneering observations, it has been discovered that the number of sunspots undergoes significant fluctuations in an 11-year cycle. However, only in the Space Age, relatively recently, have we been able to comprehend its impacts on Earth.

Energy Accumulation

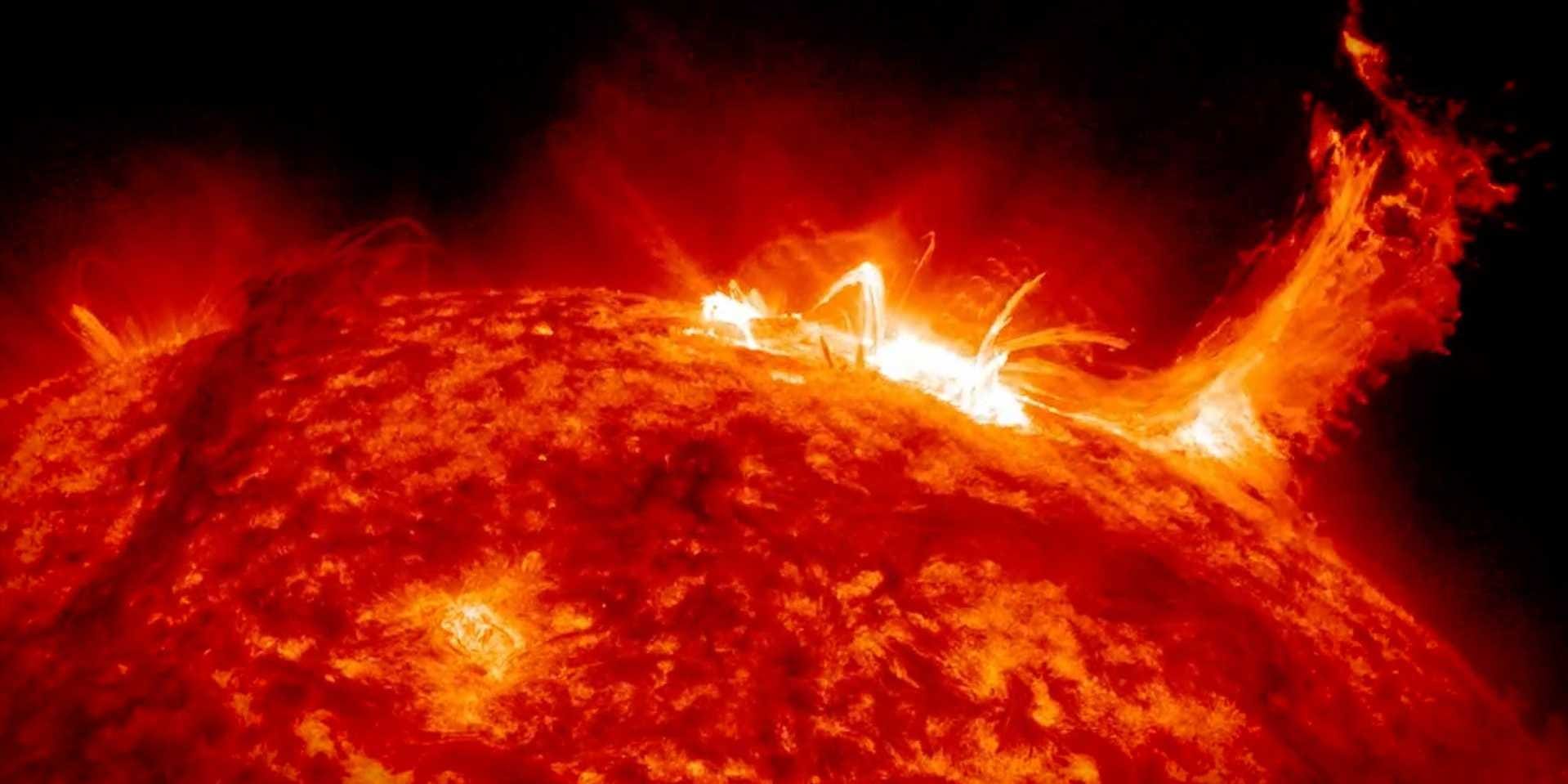

Magnetic fields serve as repositories of energy, and at times, particularly in regions like Earth’s magnetotail or in proximity to sunspots, this stored energy can transform into different forms. In the robust magnetic fields of sunspots, it may manifest as X-rays during rapid and unpredictable flares.

While sunspots and flares are situated close to the sun’s surface or its light-emitting layer, material can escape the sun’s potent gravitational field. Masses of gas, known as coronal mass ejections, can be propelled into space. A fraction of these may be directed toward Earth, giving rise to auroras and their associated magnetic phenomena upon reaching the Earth’s atmosphere. Additionally, they can contribute to the intensification of our radiation belts, potentially causing harm to satellites.

Space Weather Predictions

Initial expectations, based on long-term trends, suggested a modest upcoming solar maximum, consistent with the relatively subdued peak observed in 2014. However, in the subsequent solar cycle, we have already surpassed anticipated sunspot numbers and experienced significant magnetic storms, prompting a potential need for upward revisions in predictions.

While direct measurements from satellites in the solar wind provide only approximately an hour’s notice for impending stormy space weather, additional forecasting can be done by observing sunspots as they rotate into view during the sun’s rotation.

A solar rotation, akin to the time it takes for the moon to orbit Earth (about a month), offers an extended timeframe for prediction. Thus, if a specific sunspot exhibits heightened activity, it is likely to reappear approximately a month later.

Infrequent Storm Events

On December 14, the most potent flare of Solar Cycle 25 occurred, marking the sun’s most forceful eruption since the notable storms of September 2017.

While substantial solar storms are uncommon, it is prudent to calmly ready ourselves for potential space weather impacts, which are anticipated to peak in the coming years. Preparedness requires creative strategies, given that space weather effects can bring unforeseen challenges. In 2022, unexpected atmospheric heating led to multiple satellite losses.

As our understanding of space physics continues to advance, so too will the emerging field of space weather prediction, enabling us to safeguard our technological assets. Meanwhile, the approach of the 2025 solar maximum promises awe-inspiring auroras, accompanied by measured and reasonable concerns about potential space weather.